Continuing with our lens themed week (yesterday I wrote about basic lens information and last week I wrote about what to consider when purchasing a camera), today I’ll cover what lives in my camera bag (as well as the lenses that got booted from it).

Sorry Nikon photographers…this is a Canon post.

My Lenses

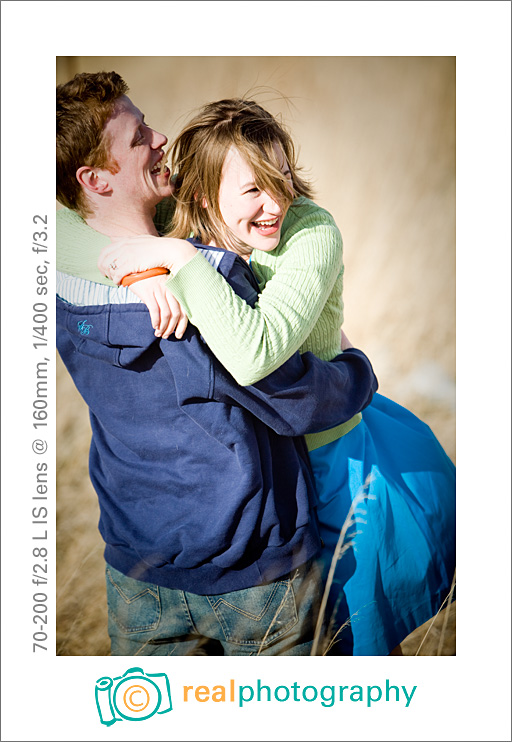

Canon 70-200 f/2.8 L IS

It is hard for me to pick a favorite lens, because I love them all, but if I had to pick just one favorite, it would probably be this one.

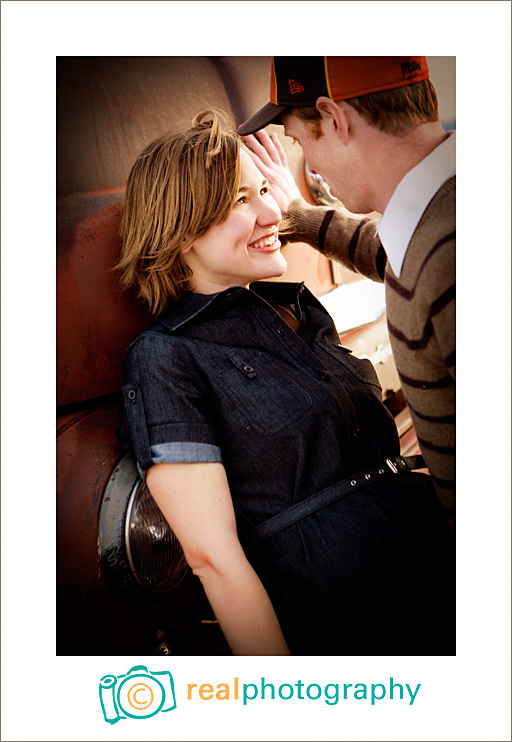

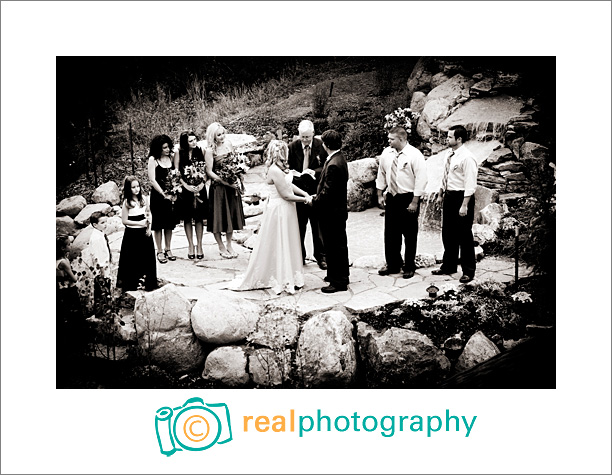

Pros: I love the beautiful bokeh it creates for portraits, and being a long (telephoto) fast (the maximum aperture is f/2.8) lens with 3 stops of image stabilization (I can take pictures in places that are three times darker), it is my best friend at indoor wedding ceremonies. I recommend it wholeheartedly to wedding photographers–I wouldn’t want to be without it. I also use it a lot for portraits–long lenses are more flattering, they condense a scene making it possible to bring a mountain or city skyline closer to your subject, and long lenses can also isolate a subject from a cluttered background better than a normal or telephoto lens.

Cons: It’s expensive. I think it would be hard to justify this lens if you couldn’t make money from it. People also complain about the weight…but I don’t think that’s a good reason not to carry the best equipment for the job. And needing to carry heavy equipment is a great reason to stay in shape. :)

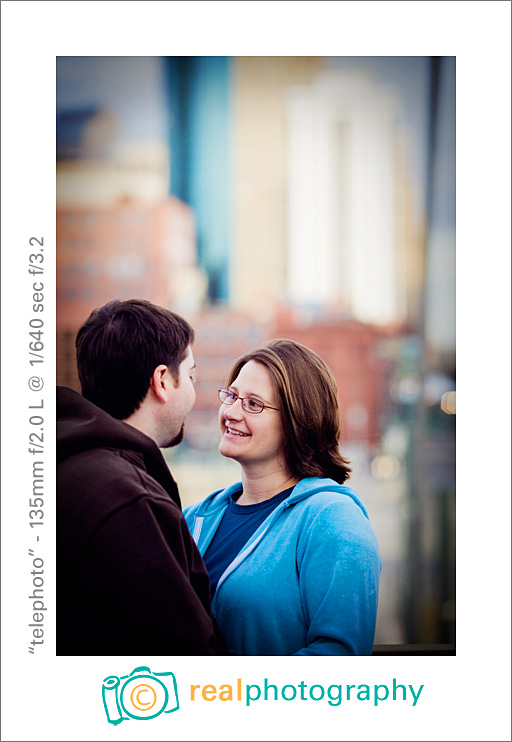

Canon 135mm f/2.0 L

Since purchasing this lens last month, it has been a disproportionate amount of time on my camera. It definitely comes a close second to the 70-200 as my favorite lens. It’s the lens I keep on my camera for taking family pictures.

Pros: This is a long fast lens, so it has all the benefits of the 70-200 (with the exception of image stabilization). It’s faster than the 70-200 (f/2.0 instead of f/2.8) so the bokeh from it is even more amazing. It’s relatively lightweight. And this is one super sharp lens. The pictures I get from it are incredibly sharp and it focuses very quickly. A fellow photographer and friend of mine calls this her “magic lens.” At $900, it’s also a fantastic deal for such beautiful quality.

Cons: This is a fantastic focal length for my style and on my full frame 5d camera, but on a 1.6 FOVCF body (rebel, 20/30/40d, etc) I can see it being too long (or too “zoomed in”) for many people’s liking.

Canon 24-70 f/2.8 L

This was our first lens, and it is a fantastic multi-purpose lens. Many pros list it as their favorite lens, or the one lens they would keep if they could only have one.

Pros: It is fast, sharp, focuses quickly, and has a great range–a perfect “every day” focal length range.

Cons: I like the 24-70 more on a 1.6 FOVCF body than I do on the 5d–it’s a little too short for my style on a full frame body (but is great in tight quarters or for groups). This is another on-the-big/heavy-side lens.

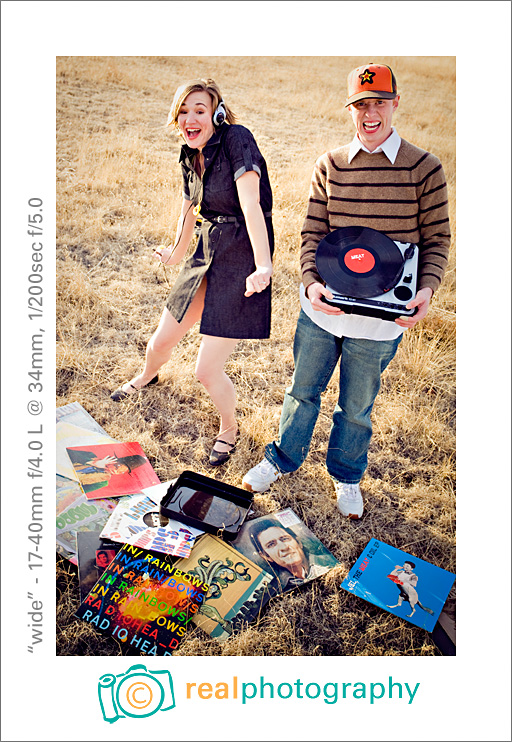

Canon 17-40 f/4 L

This is our wide angle lens, and it does a great job of that. Perfect for wide angle wedding scenes.

Pros: It is a great wide angle lens. It is a fantastic deal–$650 and fairly small and lightweight. When I need a wide angle shot, I know I’m going to get a great one.

Cons: I’m not a huge fan of wide angles (though I know they are popular right now in portraits)–I prefer the flattering telephoto lenses. So this lens doesn’t get used much.

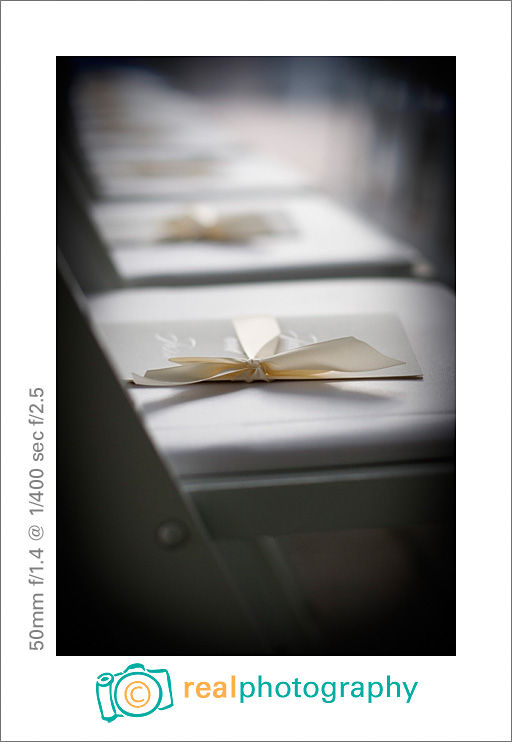

Canon 50mm f/1.4

This gets my vote for the one I recommend most to new photographers. If you are on a tight budget and can only get one lens, this is the one to get.

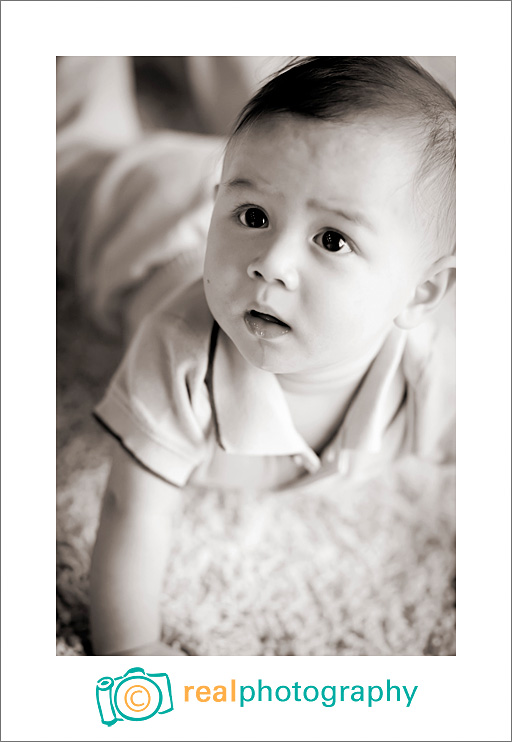

Pros: It is very fast, fantastically inexpensive ($250), and has beautiful bokeh (unlike it’s cheaper illegitimate sister, the 50mm f/1.8). This one also spends a lot of time on my camera at home. It’s wide aperture and multi-purpose “normal” focal length makes it a great bet for family photos. It is tiny and very lightweight. (And it’s the least expensive lens in my bag, so if something gets dropped or damaged from being out, at least it’s not an expensive loss!) You are also able to get very close to your subject with it–it has a minimum focusing distance of 1.5 feet, which means I can very nicely fill the frame with my little two year old subject.

Cons: Can’t think of any. Unless not having a pretty red “L series” stripe can counts as a con.

Lenses I have kicked to the curb

Canon 70-200 f/4 L

Pros: This baby is a fantastic value. One of the least expensive L lenses. It is sharp, relatively lightweight, and a great lens for traveling. We broke this one out for vacations and it was fantastic.

Cons: As a telephoto f/4 with no image stabilization, this was not a good indoor lens. The 70-200 f/2.8 IS kicked its butt, and then when we got the 135mm, we sold this one.

Canon 85mm f/1.8

Another prime lens (so far I’ve discussed the 50mm f/1.4 and the 135 f/2.0). Prime lenses are my faves and I plan on discussing the difference between primes and zooms later this week. But in short, prime lenses are usually a totally fantastic value because they only have to do one thing, and they can do that one focal length extremely well.

Pros: A lot of people like this lens.

Cons: I was not one of those people. To be fair, it IS a nice lens with great image quality and fast focusing at a great value (around $350). I think on a 1.6 FOVCF I would like this lens, but it was useless to me on the 5d. Every time I framed the shot how I wanted it, it would turn out I was too close and I’d have to take a step back. It has an almost 3 feet minimum focusing distance (compared to the 50mm’s 1.5 feet). I bought the 135mm to combat this problem (it also has a 3 feet min focusing distance, but being a much longer lens means that I can frame the shot just how I want it from that distance).

Posted in Photographer Tips